On Tawhid

By Sharjeel Imam

Image edited by Paul Hoi

A Prologue to Sharjeel Imam’s Address on Tawhid

This address by Sharjeel Imam represents an instructive addition to contemporary Muslim prison literature. As a pedagogical text that mobilizes and illuminates Urdu poetry at the intersection of politics and hermeneutics, it seeks first and foremost to educate and energize the Muslim youth about a matter of profound political-theological significance. Let me elaborate these points further with some brief notes on the text and its author.[1]

Sharjeel Imam, a well-known Muslim intellectual and activist in his mid-30s who has been imprisoned by the Indian state since early 2020 on charges of treason, writes here about the intimacy of tawhid or faith in God’s oneness and political freedom. Drawing on the idea of tawhid for projects of Muslim political action and sovereignty has of course been a signature move of Muslim modernist and Islamist movements and figures, from the late nineteenth century onwards. What is distinctive about Imam’s exposition here is his attentiveness to articulating a Muslim political theology that considers the theology of tawhid as it rejects all forms of nationalism. Imam describes his main purpose in this way: “I intend to present an introduction and explication of the idea of Tawhid in terms that would be understandable to our contemporary educated youth, and immediately relevant to their religious and political lives.”

Imam is best known of course for his leading role in spearheading protests against the draconian and racist CAA (Citizenship Amendment Act) and NRC (National Register of Citizens) laws in 2019/2020 through which he emerged as a powerful Muslim voice in India particularly among its youth. What makes Imam immensely attractive for thousands of young Muslims within and beyond India is the challenge that his thought and politics pose to liberal secular conceptions of a “good Muslim.” In its Indian variety, much like other contexts, the category of the “good Muslim” corresponds with a Muslim identity eager to erase the threat and anxiety it might generate for Hindu nationalists and Indian secularists. It is an identity that jostles for the laurel of passing as a “moderate Muslim,” uninterested in political agency and expression that might question and challenge the alleged virtues of a secular polity. Imam’s political orientation not only disrupts such a domesticated moderate Islam, it also calls into question the secular vision of the proper political place and role of Indian Muslim subjects confined to the territorial boundaries of the Indian state, or the discursive boundaries of such Indic constructs as Hindustan. Imam calls on Indian Muslims to unshackle their enchainment to all varieties of Indian nationalism, the more obviously pernicious Hindu nationalist kind but also the liberal secular kind that authorizes the moderation of Islam and Muslims through seemingly pluralist tropes like reclaiming a lost Hindustan.

It is worthy to offer the reminder that the speeches Imam delivered in early 2020 as part of the protests against the NRC and the CAA for which he was imprisoned were as scathing if not more so of the Indian secular elite, in academia and elsewhere, than of the Hindu nationalist state and its supporters. In fact, at the core of Imam’s protest was the provocative and in my view convincing claim that in their earnest attempts to depoliticize Islam and to frame Islam as a prime object of moderation the excess of which always carries the threat of spilling into violence, Hindu nationalism and varied modalities of Indian secularism have a lot more in common than what is commonly admitted. Imam provides a formidable counterpoint to South Asian secularists—in India, in neighboring Pakistan and Bangladesh, and among diaspora communities around the world—who seem ever eager to redeem the promise of (Indian-) secularism by presenting the recent rise of the BJP and Hindu nationalism as a radical departure from an otherwise tolerant Indian past, and who despite not missing any opportunity for performative solidarity with Palestine concurrently fail to call out the Indian settler colonial project in Kashmir in those terms, who celebrate the popular actor Dilip Kumar as an exemplary model of a pluralist Hindustan without flinching on the irony of a Muslim actor named Yusuf Khan having to adopt a Hindu name to gain acceptance, and who dare not broach the possibility of armed resistance as at times a necessary means for self-defense and the struggle for freedom. Sharjeel Imam is the radical ‘other’ of a domesticated, depoliticized, secularized Indian Muslim subject. This is what explains both his immense popularity among Muslim youth fed up with serving as objects of liberal secular moderation. And it also explains the unease he generates among a variety of actors, Indian and non-Indian, who remain steadfast in or at least implicitly committed to the secular belief that moderating Islam and Muslims represents a necessary virtue.

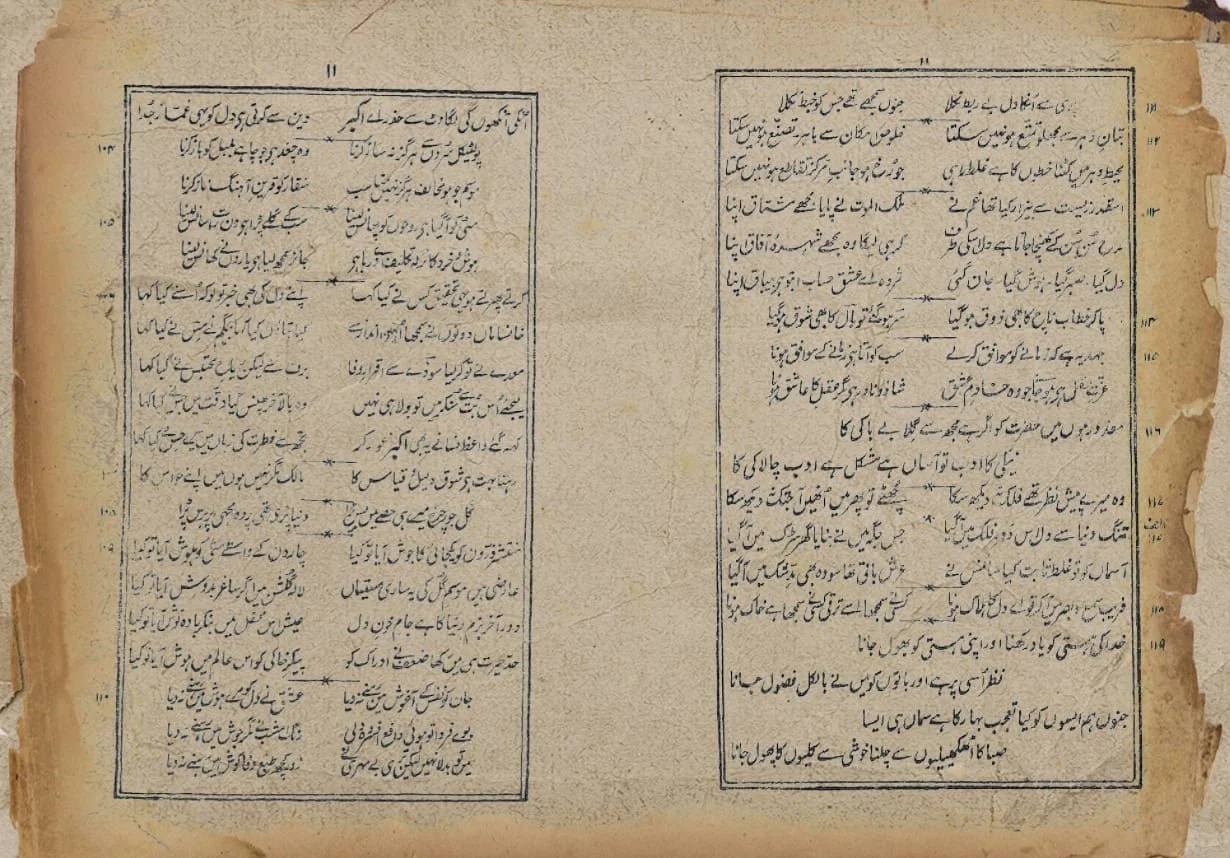

One of the remarkable and distinctive aspects of this address is the way it connects Urdu poetry, especially that of Akbar Allahabadi to the doctrine of tawhid and the rejection of nationalism, which for Imam is ultimately among the foremost symbols and manifestations of shirk (idolatry). This sentiment is especially pronounced in Allahabadi’s critique of the young Iqbal’s much heralded and quoted nationalistic poem “sare jahan se acha Hindustan hamara” (our Hindustan is better than the whole world) with the following reply translated as follows by Sharjeel Imam in his address:

Raqbe ko kam samajh kar akbar ye bol uthā Hindostān kaisā, sarā jahan hamara

Lekin ye sab ghalat hai, kehnā yahi hai lazim

Sab kuch to hai khuda ka vaham-o gumān hamarā

Finding the area too small, Akbar retorted, What is Hindostan? The whole world is ours.

But even this is wrong, we should only say, That everything belongs to God, we own nothing but our illusions

Allahabadi’s correction of Iqbal (a correction that Iqbal himself subsequently embraced) and its attraction for a figure like Sharjeel Imam both point to the significance of a radical theology that combines a notion of divine sovereignty or tawhid with a political vision that rejects the moderating force of any variety of nationalism or liberal secularism. Imam’s address thus also offers the important and often less emphasized potential of Urdu poetry to serve as a discursive vestibule for deeply theological political visions and projects. Among other things thus, Imam’s address also problematizes the popular perception that views Urdu poetry as a primarily secular mode and form of discourse. While himself imprisoned, Imam here has punctuated the path to freedom from false idols with an articulation of the power of tawhid with poetic skill and brilliance.

But though a critic of secularism and a figure whose discourse and politics challenges the dominant precepts of secular power, it is important to recognize that Imam does not escape fully the juggernaut of secularity. This is seen most clearly towards the end of his address when he seeks to establish the ‘rationality’ and rationalism of Tawhid through citing famous Western scientists like Nick Herbert and making an almost hagiographic nod towards Albert Einstein by describing him as “arguably the greatest mind of the 20th century” who spoke of his curiosity about God with the famous words: “I want to know how God created this world. I am not interested in this or that phenomenon, in the spectrum of this or that element. I want to know His thoughts; the rest are details.” Einstein’s thirst of knowledge about God may well have been sincerely held, but what must be noticed here is Imam’s desire to establish Tawhid, a concept obviously grounded in the theology of early Islam, as a thoroughly rationalist doctrine equally authorized by the language and authorities of modern science. To be sure, there is little novelty involved in making a case for the rationality of Tawhid; this is a point with plentiful precedents in varied strands of Islamic theology. But what is decisively modern and modernist in Imam’s discourse however is the citational weight and pressure of scientific rationalism as a logic of argumentation that would be appealing to wide segments of the contemporary Indian Muslim youth. Thus, even beyond India and South Asia, this address represents a very instructive primary text that displays complex modes of interaction between Islam, politics, poetry, and secular power.

SherAli Tareen

Professor, Religious Studies

Franklin and Marshall College

June 23, 2024

***

Tawhid is the fundamental principle of Islam. All other Islamic concepts, including equality, justice, and the Day of Judgement can be derived from this central tenet. The Qur’an reiterates on multiple occasions that tawhid is not a novel idea introduced by Prophet Muhammad, but is an idea as old as humanity itself and is the primary divinely-inspired message brought across ages and communities, of which we know only a handful by name.

To every people (was sent) a messenger (Qur’an 10:47)

For we assuredly sent amongst every people a messenger (Qur’an 10:36)

Nothing is said to you that was not said to the messengers before you. (Qur’an 41:43)

We did send messengers before you, some of them we mentioned to you and some of them were not mentioned. (Qur’an 40:78)

And eventually it was through Muhammad of Arabia that the most comprehensive and universal manifestation of this concept appeared. In the words of the great mystic Jalaludin Rumi (d.1273):

Nai nai ke Hamīn Bod ke mi āmad-o mī raft, Har qarn ke didim.

Tā āqibat ān shakl-e-Arab wār Bar-Amad, Darā-e- jahañ Shud.[2]

No no, it was he himself who kept coming and going; in every age, and eventually, he manifested as an Arab; became the possessor of the world.

The classical and foundational interpretations of the Qur’anic tawhid can be found in the texts of leading Islamic scholars like Imam Ghazali (d. 1111) and Shah Waliullah Dihlavi (d.1762). And one can find more dynamic and innovative interpretations among Muslim Sufis and ‘Ārifs (mystics) such as Maulana Rumi, ‘Abdul Qadir Bedil (d.1720), Akbar Allahabadi (d.1921) and Allama Iqbal (d.1938).

In this address, I intend to present an introduction and explication of the idea of tawhid in terms that would be accessible to our youth and immediately relevant to their religious and political lives.

Traditionally, tawhid means belief in the idea that there is only one supernatural entity worthy of worship who has created all that exists and who sustains all that exists. All creations, humans and others, seek sustenance from His mercy and are bound by His orders. Those who have been granted freedom of choice in this grand order will be held accountable by Him.

These ideas are encapsulated in the first three verses of Qur’an:

…

Praise be to God; the cherisher and sustainer of the worlds. Most gracious, most merciful, Master of the Day of Judgement.

This concept is further elucidated in a famous Qur’anic phrase, which is also the first half of the first kalima:

La ilaha illa-allah

No God but the God.

The Arabic word ilah means deity and al-lah is believed to be the Short for al-ilah i.e., the deity. There is no deity but the deity. The recursive definition of this central tenet hints at the dynamic nature of tawhid.

This declaration is a negation of all false gods. There is nothing like Him.

And there is none like unto Him. (Qur’an 112:4) And no one can comprehend or see Him:

No vision can grasp him. (Qur’an 6:103)

There is nothing in this space-time complex, no tangible or comprehensible phenomenon, that can be considered to have devotional claims on humans. The ultimate is beyond the tangible and comprehensible, and He alone deserves our submission.

Akbar Allahabadi, (d. 1921), one of the greatest Urdu poets and ‘ārifs whom Iqbal called Lisān- ul-‘Asr (voice of the age) expresses this idea in his verses:

‘Aql meñ jo ghir gayā lā-intihā kyūñ kar huā

Jo samaj meñ aa gayā phir wo ḳhudā kyūñ kar huā.[3]

That which can be comprehended by the intellect, cannot be limitless, that which can be understood by us, can never be God.

…

Falsafī ko bahs ke andar ḳhudā miltā nahīñ Dor ko suljhā rahā hai aur sirā miltā nahīñ.

The philosopher is unable to find God in his arguments. He disentangles the rope, but can’t find the origin.[4]

As soon as you think you have figured it out, you are wrong. The path towards God is a never-ending journey of humanity towards greater and greater consciousness of existence. The Qur’an explains it in the story of Abraham – as a child he thinks that the moon is the deity; but when the moon sets, the sun is the deity; but when the sun sets, he says:

“O my people, I am indeed free from your (guilt) of giving partners to God.” (Qur’an 6:76,77,78)

Similarly, it is the destiny of humans to reject one false god after another in our potentially endless journey towards greater realization of reality. As Iqbal writes in a Farsi verse:

Hasil-e umram seh harf ast

Tarashidam, parastidam, shikastam[5]

My life can be described in three words

I carved it, I worshiped it, I destroyed it.

Here both Iqbal and Allahabadi allude to the dynamic nature of tawhid-based consciousness: every age will throw new idols to be destroyed, new false gods to be demystified, internal as well as external; this is the essence of tawhid.

The opposite of tawhid is shirk which means associating partners with God; it is an impediment in the straight path of Islam. I agree with the spirit of Allama Iqbal's articulation, where without essentializing any religious community, he engages in a conceptual conversation on categories:

Kāfir-e Bedār dil pish-e sanam Beh zi dindāri ki khuft andar haram[6]

The pagan idol worshiper with a living heart,

Is better than the religious man who sleeps in the Haram.

Humans have historically attached supernatural attributes or magical qualities to natural phenomena to worship the sun, fire, God-men, or shrines. Today, men of science engage in idolatry as well through their fetishization of positivist methods and mechanical determinations which expose their lack of grounding in tawhid.

There is also the complicated problem of literalism. Prophets and Messengers of tawhid are deified through literalist, ahistoric, and reified readings of their statements, experiences, and actions. In the context of Islam, static interpretations and readings of the Prophet's traditions strip them of their dynamic spirit of tawhid. Akbar Allahabadi reminds us:

Yāroñ ne but shikan ko but hi banā ke chorā[7]

The destroyer of false Gods has been himself converted into a false God.

Or, as Iqbal writes in “Saqinama,” one of the most profound poems ever written in Urdu:

Tamaddun tasawwuf sharī. at-e kalām

Butān-e-‘ajam ke pujārī tamām

Haqīqat ḳhurāfāt meñ kho gaī Ye ummat rivāyāt meñ kho ga.[8]

Culture, mysticism, shariat (law), theology,

All of them have become worshippers of false Gods,

The truth has been lost in the bundle of superstitions,

This ummat has been entangled in the web of traditions

Asadullah Ghalib (d. 1869) declared himself a believer of tawhid, a muwahhid, rejecting the attachment to outdated traditions:

Ham muwahhid haiñ hamārā kesh hai tark-e-rusūm Millateñ jab mit gaīñ ajzā-e-īmāñ ho gaīñ[9]

We are believers of tawhid; it is our duty to abandon traditions of communities who have gone extinct, but become a part of our faith.

***

All forms of prejudice against fellow humans derive from shirk and are incompatible with the notion of tawhid.

The Qur'an reiterates this point many times:

Mankind was one single nation. (Qur’an 2:213)

Mankind was but one nation but differed (later) (Qur’an 10:19)

O mankind! We created you from a single (pair) of a male and a female, and made you into nations & tribes, that you may know each other (not that you may despise each other). Verily, the most honoured of you in the sight of God (he who is) the most righteous of you. (Qur’an 49:13)

The verse says the most honored amongst you is the one most intense in taqwa (God-consciousness). Taqwa means preserving and guarding oneself from evil deeds and fearing God, especially fearing displeasing him. Only complete faith in tawhid and grasping its universal nature can lead one to perfect their taqwa. The best among us is the one who is most righteous (the one most intense in taqwa), not the one of a particular tribe or nation.

The universality of tawhid exceeds place, race, people, or geography. This is why when the young Iqbal wrote the nationalist poem “sare jahan se achha Hindostan hamara” (“our Hindustan is better than the whole world”), the old seasoned Akbar Allahabadi pointed out to him:

Raqbe ko kam samajh kar akbar ye bol uthā Hindostān kaisā, sarā jahan hamara

Lekin ye sab ghalat hai, kehnā yahi hai lazim Sab kuch to hai khuda ka vaham-o gumān hamarā[10]

Finding the area too small, Akbar retorted, What is Hindostan? The whole world is ours.

But even this is wrong, we should only say,

That everything belongs to God, we own nothing but our illusions.

Iqbal eventually realized his mistake and wrote a strong critique of nationalism, the latest false God that humanity has encountered. In his poem “Wataniyyat” (“Nationalism”), he says:

In taza khudāon mai badā sabse watan hai Jo pairhan iska hai wo mazhab ka kafan hai

Nation is the biggest of modern false Gods, Its clothing is stitched from religious shroud.[11]

It is also important to note that even though the Qur’an as the final message to mankind completes and perfects the Din, the Qur’an is clear in warning against religious supremacy.

Those who believe (in the Qur'an), and those who follow the Jewish (scriptures) and the Christians & the Sabians - Any who believe in God and the Last Day and work righteousness, shall have their reward with their Lord: on them shall be no fear, nor shall they grieve. (Qur’an 2:62)

The Qur’an makes it clear that faith and righteousness alone, and not membership to any community or sect, decides the "reward" of the individual. As Abdullah Yusuf Ali lucidly puts in his commentary of one of these verses (Qur’an 5:72):

“As God's message to one, Islam recognizes true faith in other forms, provided that it be sincere, supported by reason, and backed by righteous conduct."ˀ

***

Tawhid implies the divine and supernatural origin of life; the concept of the sanctity of life also derives from the belief in such origin which disrupts the mechanistic materialism of positivist science.

As Iqbal says in “Saqinama”:

Yeh ‘ālam ye but-ḳhāna-e-shash-jihāt isī ne tarāshā hai ye somnāt

This world, this six-directional (3-d) idol house,

Life itself (through evolution) has carved this temple.

Teri āg is khākdān se nahiñ

Jahañ tujh se hai tu jahan se nahiñ[12]

Your fire does not come from this material world,

The (observable world) is from you, you are not from the (observable world).

And another brilliant couplet by Iqbal in Javednama:

ān-chi dar ādam ganjad ‘ālam ast

ān-chi dar ‘ālam na ganjad ādam ast[13]

what accumulates in a human is the universe,

what doesn’t fit in the universe is a human.

When Albert Einstein, arguably the greatest mind of the 20th century, says:

“I want to know how God created this world. I am not interested in this or that phenomenon, in the spectrum of this or that element. I want to know His thoughts; the rest are details.”[14]

I am reminded of Iqbal's daring couplet:

Ye jannat mubārak rahe zāhidoñ ko Ki maiñ āp kā sāmnā chāhtā huuñ

May the pious enjoy the heaven,

I want nothing less than an encounter with You.

Through tawhid we can move beyond the two extremes: the reduction of life into a mechanistic play of local phenomenon (i.e. materialism) or a kind of superstitious spiritualism which essentializes every fleeting and every recurring coincidence and idolizes the hitherto unexplained phenomenon. Tawhid is the only rational way out of both superstition and nihilism.

[1] For a fuller analysis of Sharjeel Imam’s political discourse and of its significance to the interaction of religion and secularism in contemporary India, see the epilogue of my book Perilous Intimacies: Debating Hindu-Muslim Friendship after Empire (New York: NY: Columbia University Press, 2023).

[2] Jalaluddin Rumi, Masnavi-yi Ma‘navi

[3] Akbar Allahabadi, Kulliyat-i Akbar Allahabadi

[4] Ibid

[5] Muhammad Iqbal, Kulliyat-i Iqal Farsi

[6] Ibid.

[7] Allahabadi, Kulliyat

[8] Muhammad Iqbal, Saqi Nama

[9] Asadullah Ghalib, Diwan-i Ghalib Jadid

[10] Allahabadi, Kulliyat

[11] Muhammad Iqbal, Kulliyat-i Iqal

[12] Muhammad Iqbal, Saqi Nama

[13] Muhammad Iqbal, Javednama

[14] Quoted in Nick Herberg, Quantum Reality